Navajo Pictorial Weaving [SOLD]

Forward to Friend

Forward to Friend

- Subject: Native American Textiles

- Item # C3602X

- Date Published: 1975

- Size: 32 pages SOLD

NAVAJO PICTORIAL WEAVING

By Charlene Cerny

Forward by Joe Ben Wheat

Published by The Museum of New Mexico Foundation for The Museum of New Mexico

Condition: very good to excellent condition

Paperback exhibit catalog, 32 pages. First Edition, 1975. Illustrated with black and white and color photographs of Navajo pictorial weavings.

This publication arises from an exhibition presented at the Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe, in 1975-1976

From the Foreword by Joe Ben Wheat

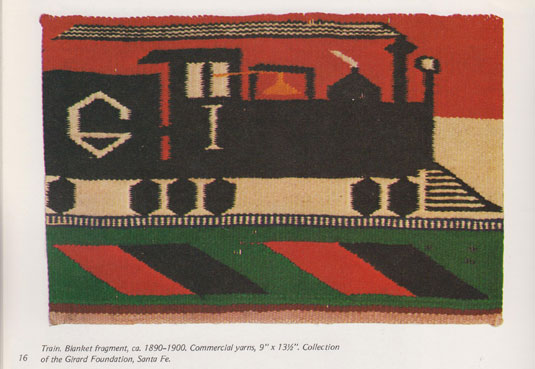

“When the Navajo weaver mastered tapestry techniques, she gained the means of producing any decorative motif she desired. The bold terraced patterns of classic blankets and the serrate diamonds of later times are products of a tapestry technique that differed in no vital way from that of the fine tapestries of Europe. From the small birds in the Chief White Antelope blanket to ‘soap label’ copies of railroad trains, to the fully composed pictorials of today, there have always been a few weavers who went beyond the standard geometric designs to depict something that intrigued or amused them, or to create a picture expressive of the life around them. Horses and cattle, hogans and schoolhouses, cornstalks and birds, the land itself, even tigers and kangaroos seen in a traveling circus or a TV commercial—these are the stuff of yesterday’s pictorials and today’s. We do not know when a Navajo weaver first included a pictorial element in her tapestry, but it was long ago, and there have been many since.”

From the Book:

Simply by virtue of their representational subject matter, Navajo pictorial weavings depart from the strictly geometric designs we usually associate with Navajo blankets and rugs. They are little-known outside the Southwest and seldom discussed. For whatever reasons-perhaps because of their relative scarcity or their outmoded classification as “tourist art” - few attempts have been made to come to grips with the “pictorial” as a Navajo craft form.

The only representational weavings traditionally excluded from the pictorial category are those depicting motifs of a ceremonial nature, such as “yei,” “yeibichai,” and sand paintings. Typical subject matter for a pictorial might be a landscape scene, animals, a product trademark, a flag, or a pickup truck. The Navajo pictorial, then, stands as a significant document recording the individual impressions of a single weaver in her day, and of the influences affecting her existence. Pictorials thus offer a rare glimpse into Navajo secular life—one which is oftentimes unavailable even to the present-day tourist in Navajo country, where, despite the superhighways, much of the Reservation remains remote and foreboding.

The pictorial category is a thematic one only; the technique used in weaving pictorials is the same as that found in other types of Navajo weavings. A simple, upright frame loom is utilized to produce the tapestry-weave characteristic of most Navajo blankets and rugs. In this type of weave, weft threads conceal warp threads, and the design is formed by the wefts (i.e., the textile is “weft-faced”). The weft is discontinuous, which is to say that a single thread is not necessarily carried across the whole warp. A single weft may be worked only part way across, with wefts of other colors successively placed to fill out the row. Numerous rows thus produce color areas which grow into recognizable shapes and forms.

THE PICTORIAL TRADITION

What is believed to be the earliest extant example of a pictorial motif in a Navajo weaving dates back to the late 1850's or early 1860's. The Chief White Antelope blanket, removed from the body of a Cheyenne warrior following the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, is almost entirely geometric, but incorporates four tiny birds into its otherwise conventional classic design.

But it is not until the period from 1880-1900 that the pictorial tradition begins to take root and flourish. This era was marked by a frenzied growth of American penetration into the Southwest. As Amsden observes, foreign influences on the Navajo weaver at this time were intense:

An Army officer wants “something fancy” and makes a sketch of his idea to guide the weaver. A trader's wife appears in a figured dress, or lays on her living room floor a rug fresh from an eastern factory. The trader exhorts his weavers to take heed of the new market, and displays catalogues of the latest linoleum patterns by way of inspiration. Soldiers in gaudy uniform and impressive insignia ride briskly about. Railroad trains come puffing and screaming down the long slope of the continental divide. The whole world of the Navajo is born again.

The proliferation of trading posts during this period, and the arrival of ranchers and settlers, and the railroad in 1881, thus provided rich new sources from which the weavers could draw...

- Subject: Native American Textiles

- Item # C3602X

- Date Published: 1975

- Size: 32 pages SOLD

Publisher: